The battle fought at Blood Gulch seems finally coming to an end. After four years of serialization Rooster Teeth Productions of the celebrated machinima Red vs. Blue: The Blood Gulch Chronicles (RvB for short) has announced to conclude the series with its 100th episode. RvB has claimed thousands if not millions of fans around the globe; it was the first breakthrough for machinima to reach the public outside of gaming community. Paul Marino (co-founder and the executive director of the Academy of Machinima Arts & Sciences) remarks the incident:

The battle fought at Blood Gulch seems finally coming to an end. After four years of serialization Rooster Teeth Productions of the celebrated machinima Red vs. Blue: The Blood Gulch Chronicles (RvB for short) has announced to conclude the series with its 100th episode. RvB has claimed thousands if not millions of fans around the globe; it was the first breakthrough for machinima to reach the public outside of gaming community. Paul Marino (co-founder and the executive director of the Academy of Machinima Arts & Sciences) remarks the incident:‘Beginning as what was to be a small six episode mini-series in the spring of 2003, The Blood Gulch Chronicles became the world's first extremely viral Machinima work, which spread like wildfire across the net, knocking out their hosting provider due to the massive amount of file requests. Over time, the series became increasingly popular, sustaining a loyal community that totaled into the hundreds of thousands of viewers - the download counts reaching into the millions on a per episode level. With a consistent delivery of high-quality episodes over the course of 5 seasons, it also allowed 5 friends from Austin, Texas to leave their day jobs in order to make Machinima for a living. Rooster Teeth not only made headlines for making successful Machinima, they also broke ground how to create a successful web-based entertainment brand.’ (Marino, 2007).

The story of RvB showed how a bunch of game fans turned their creativity into high-quality media production, steered countless eye-balls away from the mainstream media and become economically self-sustainable. Their success, compare to the underground small scale fanzine culture lived through the 1920s-1980s (Poletti 2005) was contrasting. Although it is not to assume all fan productions today could be as successful as RvB, and they do still face the numerous constrains similar to those faced by the earlier fanzine practitioners, the living condition for fan community as a whole has been noticeably improved.

Henry Jenkins contrasts the context for which the fans engage in creative production in terms of ‘textual poachers’ and ‘convergence culture’ (terms coined after his books): fans as ‘Textual Poachers’ live in ‘a world where fan culture was largely marginalized and hidden from view’; whereas fans in ‘Convergence Culture’ are privileged in ‘a world where fan participations are increasingly central to the production decisions shaping the current media landscape’(Jenkins 2007). In short, the environment for fan participation is much more understood and somewhat appreciated than before.

The emergence of convergence culture is not a natural occurrence, nor is it simply the result of technological advancement, but a process that involves renegotiating social and economical relationships between producers and consumers (Jenkins, 2004). The fans - those who ‘refuse to simply accept what they are given, but rather insist on the right to become full participants’ (Jenkins, 2006), are the most active segment of consumers who continue to assert their stake in this process.

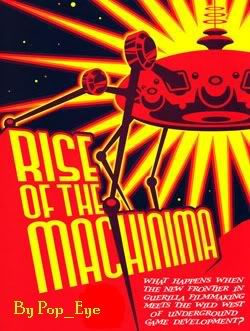

In this essay we will use machinima as a case study to discuss two areas where fan participation has demonstrated significance (click on the links below to view the respective section):

1) Corporate ownership vs. Value added by fan community

2) Narrative Structure and Storytelling

And finally in conclusion, we will discuss some of the impact fan community has had on the outside world, i.e. those less participated media consumers.

Bibliography

- JENKINS, H. (2004) The cultural logic of media convergence. International journal of cultural studies, 7, 33-43.

- JENKINS, H. (2006) Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry. Convergence culture : where old and new media collide New York, New York University Press.

- JENKINS, H. (2007) When Fandom Goes Mainstream... Confessions of an aca-fan. Retrieved 23 May, 2007, from http://www.henryjenkins.org/2006/11/when_fandom_goes_mainstream.html#more.

- Marino, P. (2007). "Rooster Teeth winds down Red vs. Blue: The Blood Gulch Chronicles " Retrieved 22 May, 2007, from http://blog.machinima.org/2007/04/rooster-teeth-winds-down-red-vs-blue.html#links.

- POLETTI, A. (2005) Self-publishing in the Global and Local: Situating Life Writing in Zines. Biography, 28, 11.